A Travelogue of Modern Iran: From the Caspian to the Persian Gulf

The full version, including what happened in Tehran on several fronts – IRGC, nanotechnology, academic debates – of the column originally published on Sputnik.

By Pepe Escobar at VKontakte.

ON THE ROAD IN IRAN – The International North South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) is one of the most crucial geoeconomic/infrastructure projects of the 21st century. It unites at its core three key BRICS nations – Russia, Iran and India – branching out to the Caucasus and Central Asia. When fully operational, the INSTC will offer a full trade/connectivity corridor sanctions-free, cheaper and faster than the Suez canal to a great deal of Eurasia. The geoeconomic consequences will be staggering.

The International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC): The New Silk Road Shaking Up Global Trade. A 7,200km sanctions-proof trade route that could replace the Suez Canal for Eurasian trade.

To re-visit Iran in these times of geopolitical trouble, relentless “maximum pressure”, red lines on uranium enrichment and bombing threats could not be more pressing – and enlightening.

These have been only a few of the highlights of the past two weeks:

- A visit to the Iran Nanotechnology Innovation Council . Iran is a nanotechnology superpower, among the Top 5 in the world, exporting products in different domains – from health care to agriculture – to over 50 nations.

- A serious round table at Imam Sadiq University, open to PhD students in several disciplines, which started as an evaluation of Iran-US relations and then amplified to examine the twists and turns of the New Great Game in international relations, essentially pitting the declining but ever dangerous Empire of Chaos and the drive towards Eurasia integration.

- A visit to the IRGC Aerospace Museum – exhibiting several of Iran’s military breakthroughs, from generations of Shahed drones to Fatah missiles, where I posed to Brig Gen Ali Balali a key question on whether Operation True Promise 3 in response to Issrael, which has been postponed, will be eventually carried out. His nuanced answer was diplomatic but firm. As correctly translated from Farsi, he said, “General Hajizadeh stated that the operation will be carried out at the right time. Any other claims are just external noise. As we’ve demonstrated up to now, we have never retreated — not from our rights, and not from our red lines. I’m not in a position to say if TP3 is ready or not, for that the responsibility lies with those in charge, namely the General Staff of the Armed Forces, who will make that call. Whenever the time comes, they will notify us — and by ‘us’, I mean the Armed Forces & the Aerospace Division.”

- A serious Shi’ite theology discussion hosted by CEO of Press TV Ahmad Noroozi with master theologian Fareed Eftekhari – touching the abyss of Western spiritual nihilism; whether there can be a way out; and the search for Oneness intrinsic to sufism. That was complemented by another dinner discussion with serious Persian brainpower – in filmmaking, academia and once again Shi’te theology, via iconoclastic independent thinker Blake Archer Williams (his pen name), who actually provided the best definition of wilaya, without which is impossible to understand how the Islamic Republic of Iran works (don’t expect Western warmongers to make the effort).

In essence, Wilāya…can mean 1. regent, sovereign, lord and master; 2. patron, guardian, protector, custodian. Its plural form is awliā: those of God’s creatures who have spiritual affinity and propinquity to Him, inclusive of prophets and Imāms. The walīy is the divinely-appointed Divine Guide, Just Ruler, and Guardian-Sovereign (walīy al-amr) of the affairs of the community of true believers (the mu’minīn).

Williams explains how “Wilāya has a two-fold essence: the walīy is chosen by God because of his spiritual affinity and propinquity to Him. This preeminence gives the walīy’s soul a certain sacred luminosity (due to his sacral propinquity), which in turn draws people to him, as it responds to their need for guidance and to their appreciation of beauty and nobility of character. Thus, wilāya has a top-down function [being appointed by God due to his preeminence], and at the same time, has a bottom-up function (being drawn to and appointed by the people to lead them on their common sacred purpose of their self-surrender to God’s will (islām).” Both of these aspects (the theocratic and the democratic), as Williams stresses, must be present because, “paradoxically, wilāya is meritocratic and democratic at one and the same time.”

By then it was time to hit the road. And there was only one way to go: to explore the INSTC on the ground, from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf and the Makran coast in Sistan-Baluchistan all the way to Iran-Pakistan border.

Total connectivity: highway, mosque, bazaar

By an auspicious turn of events, the old school reportage/investigation actually became the plot line of a documentary, produced in Iran, shot by an outstanding crew of 6, and to be broadcast in several parts of Eurasia, including Russia and China. Here we offer the broad strokes of our travel to the heart of the INSTC.

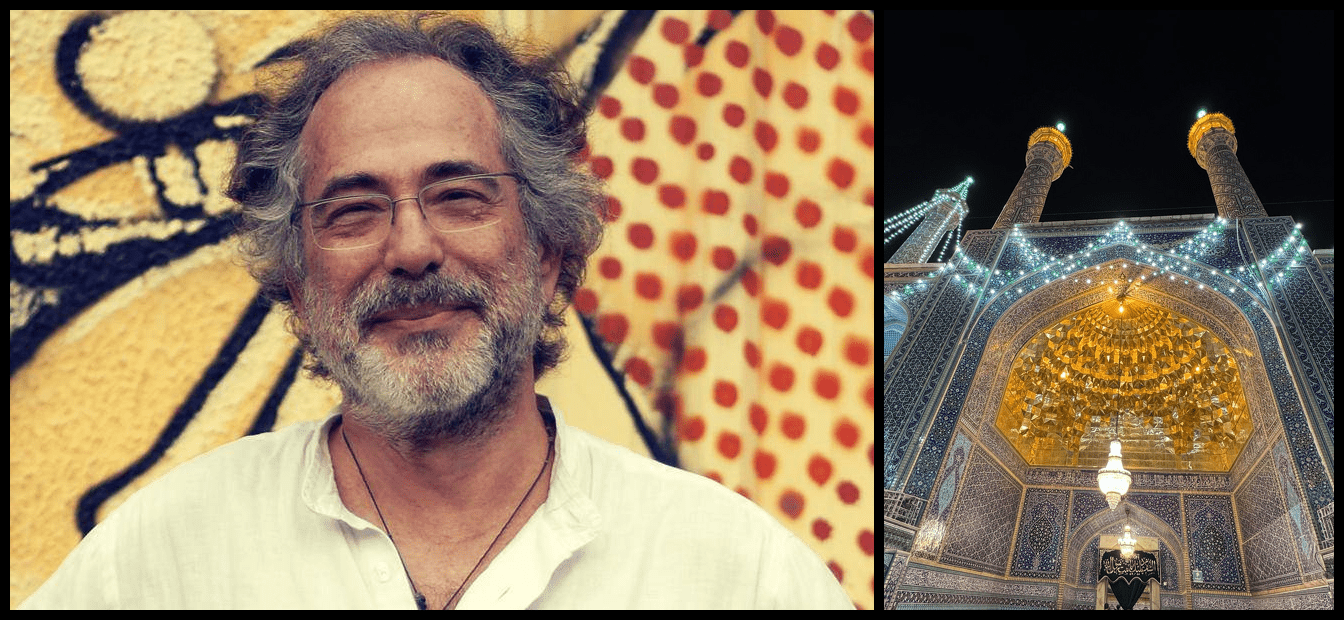

Tehran: (L): With serious Persian brainpower – in film making, academia and Shi’ite theology. (R): At a very serious theology, Western nihilism and sufism discussion, with, among others, Alastair Crooke and George Galloway.

We started with a series of interviews in Tehran, with Central Asia analysts and most of all Mostafa Agham, the top expert of Behineh Tarabar Azhour, a transportation and logistics firm specialized in Eurasia railway corridors. These analyses offered contrasting points of view on where the INSTC should go next and what are its main challenges.

Travel along Iran’s main artery, from Tehran to Bandar Abbas, was a must – as it will conform the trans-Iran north-to-south highway axis of the corridor. That doubles of course as a cultural and spiritual pilgrimage, which in our case featured plenty of auspicious overtones.

Isfahan: (L): On the road to Isfahan, not far from Natanz nuclear plant. (R): The mesmerizing ‘Royal’ mosque.

Isfahan: (L): Isfahan architectural magic. (R): In the most astonishing square in the world.

We arrived at fabled Isfahan past sunset, which allowed us to visit the Masjed-e Shah – or “Royal” – mosque virtually undisturbed. The Royal mosque – one of the highlights of Islamic architecture – sits on the south side of the Naghsh-e square in Isfahan, one of the most extraordinary public squares in the history of art and architecture, rivaling, and arguably surpassing San Marco in Venice.

A visit to the Isfahan bazaar is also inevitable. I was looking for an old friend who sold nomad carpets – in the end, because of slow business, he relocated to Portugal – just to find his sort of heir, young, energetic, who apart from pointing me to a spectacular, rare tribal rug from northeast Iran close to the Afghan border, gave me a crash course on the effects of sanctions and the perpetual demonization of Iran in the West (“Turkey has 40 million tourists; we have two or three”). Isfahan’s neat and extremely organized bazaar offers quality handicrafts to rival Istanbul, but there’s essentially domestic tourism, sprinkled with a few foreigners mostly from Central and South Asia and some from China.

(L): Tehran. At the IRGC Aerospace Museum; reverse-engineering an American missile. (R): Qom. At the Fatima Masumeh shrine. (leading article banner is at the Fatima Masumeh shrine at 2 in the morning)

On the way back to Tehran we learned that, being a Tuesday, the revered Haram of Fatima Masumeh, the daughter of the 7th Imam Musa, in Qom was open all night. Nothing prepares the pilgrim for an arrival at nearly two in the morning to an apotheosis of gold and crystals in the heart of Qom, Iran’s second most sacred city after Mashhad. Only a few pilgrims paying their respects, some strolling around the shrine with their families or reading the Quran. A moment of quiet illumination.

Southern Caspian Sea: (L): Fishing at the Caspian, outside Bandar Anzali. (R): On the Caspian corridor: from Astrakhan to Bandar Anzali.

Afterwards it was time to hit the Caspian, and the port of Bandar Anzali, the proverbial “international bridge” where, in theory, cargo ships from Astrakhan in the Russian Caspian, as well as other Caspian-bordering states will start arriving en masse via the INSTC. In Bandar Anzali, Iran essentially imports petrochemicals, construction materials, minerals, and iron products and exports grains (soybeans, corn, barley, wheat) and crude oil.

In Tehran, Mostafa Agham, the connectivity expert, had explained in detail that perhaps the multimodal drive of the INSTC across the Caspian may not be the best idea. The Russians prefer to build a railway bordering the western margins of the Caspian; and another possibility is to use a network of already functioning railways from southcentral Russia, across Kazakhstan all the way to Aktau, by the Caspian, and then connecting across Turkmenistan to Tehran.

It’s only via a close up on Bandar Anzali that one understands the Russian rationale. One of our cameramen, in delightful broken English, coined an instant hit: “Port no exist”. Translation: the infrastructure has not been upgraded in decades, which brings us to the devastating effects of sanctions, visible in several nodes of Iran.

That was extra evidence supporting the fact that China will have a lot of work to do as part of the 25-year strategic partnership with Iran, signed in early 2021: a comprehensive agreement between two civilization-states where energy-for-infrastructure is a central plank amidst scores of BRI-related projects.

The Persian Gulf: (L): Entering Bandar Abbas port, Iran’s key INSTC port. (R): From Bandar Abbas, the Strait of Hormuz is 39 km that way.

Break to the border!

Bandar Abbas, in the Persian Gulf (italics mine), is a completely different story. That’s Iran’s main port, and a key node of the INSTC, to be connected to Mumbai and already connected to the big ports in eastern China. We had all the hard-to-get necessary permits to explore Shahid Rajae-i Special Economic Zone, crammed with containers from shipping firms such as West Asia Express and unloading scores of Chinese container cargoes. The uber-strategic Strait of Hormuz is only 39 km to the south. A few days after our visit, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian went straight to the point, referring to proverbial Trump threats: “Block our oil, and we’ll block the world’s energy.” Iran can do it – in a flash; were that to happen, the collapse of the global economy is guaranteed.

Additionally, port authorities explained that the recent explosion on Shahid Rajae-i – attributed to “negligence”, still under investigation and somewhat mired in controversy – was not in the port itself, but in a storage area 10 km away.

Sistan-Baluchistan: (L): The Makran coast. The fishing port of Beris. (R): At a kapar – the Sistani version of a yurt.

From the Persian Gulf we fly to the Sea of Oman – and infrastructure problems ride again: there are only two flights a week. We arrive at a minuscule military airport outside the future superstar of the INSTC: the port of Chabahar in Sistan-Baluchistan province. Baluchis are exceedingly cool, cousins to the ones on the other side of the border, in Pakistan. In bustling Chabahar, the lineaments of a boom town are quite visible.

A long walk in the port side by side with Alireza Jahan, a logistics expert and then a conversation with Mohammad Saeid Arbabi, the Chairman of the Board and Managing Director of the Chabahar Free Trade Zone could not be more enlightening.

Jahan explains how Chabahar is essential to Iran’s East Axis, serving over 20 million people not only in huge Sistan-Baluchistan but also three other Khorasan provinces, and further on to Kerman. So Chabahar is the port for an enormous hinterland, while its competitor, Gwadar in the Arabian Sea in Pakistan, only 80 km away or so, is virtually isolated.

Jahan also explains Indian investment. Tehran is investing heavily in the infrastructure and superstructure of Chabahar port, while India is investing in equipment: the Italian cranes around the port came from India. Arbabi, at the Free Trade Zone, expands on the international profile of Chabahar, which will be an absolutely key node not only for landlocked Afghanistan but also the Central Asian “stans”.

And that brings us to the local highway saga: Chabahar to Zahedan, in the Afghan border, 632 km, already an “acceptable road”, and with a companion railway to be built within the next three years, everything 100% financed by the Iranian government.

Progress at the port is steady – slowly but surely. For the moment Chabahar receives three ships from India a month and two ships from China, plus three from the Persian Gulf. The distance from Mumbai is only 4 days, and from Shanghai, 15 days. The potential for expansion is limitless.

From Chabahar, it’s on the road bliss along the spectacular, strategic, oil-drenched, semi-desert Makran coast, bordering the immaculate Sea of Oman all the way to the Arabian Sea. History looms large: this is where Alexander the Great lost as much as 75% of his army to dehydration and starvation when he was retreating across the desert to Macedonia after his tortuous two-year invasion of India.

Sistan-Baluchistan: (L): The spectacular – virgin – Makram coast. All the way to the Iran-Pakistan border. (R): WELCOME TO THE IRAN-PAKISTAN BORDER. I finally made it – by boat! Thanks to Commander Chabad, born in Chabahar, and his little brother and second-in-command. Iran is around sunset. Pakistan is ahead of us, to the left. No CIA and MI6, no instrumentalized Salafi-jihadis disguised as Baluchi nationalists. Only the silence and beauty of the Sea of Oman meeting the Arabian Sea.

Due to a concert of economic and ecological reasons, there have been plans for quite a while to relocate the capital, Tehran, to the Makran coast. Chabahar in this case would be the ideal candidate: free port, INSTC connectivity between Central Asia and the Indian Ocean.

India – which needs to step up its geoeconomic game – has noticed it. China as well. Even though China is not formally part of the INSTC, Chinese companies are bound to invest massively in Chabahar – the de facto key node for South Eurasia integration – as part of yet another vector of the Maritime Silk Road.

I had been trying for 20 years-plus to reach the Iran-Pakistan border, from either side. It was always an impossibility due to serious security reasons. I finally made it – by boat, thanks to teenage Commander Chabad, born in Chabahar, and his little brother and second-in-command.

As we sailed away from the small fishing port of Gwat, Iran was located around sunset and Pakistan ahead of us, to the left, in what the locals call “Pakistan beach”. No CIA and MI6; no instrumentalized Salafi-jihadis disguised as Baluchi nationalists; no sanctions; no maximum pressure; no bombing threats. Only the majesty of Nature, the silence and the beauty of the Sea of Oman embracing the Arabian Sea.